Research

Bedrock Anisotropy and Meander Growth

Project Overview

Put simply, bedrock meandering rivers are sinuous channels that flow directly over bedrock or a very thin sediment cover. They are supply-limited, which means water's transport capacity always exceed sediment supply, so the river can remove sediment faster than it's being supplied to the system, and morphological change depends on how much sediment is available in the system.

Bedrock rivers can be found in a variety of environments and, due to the limited sediment cover, are capable of incising directly into the underlying rock over geologic timescales.

As a result, they preserve valuable records of rock uplift, fault activity, and long-term landscape evolution (e.g., strath terraces).

However, the mechanisms by which bedrock channels meander have only been partially explored.

While some maintain a stable single-thread form for millions of years, others transition more rapidly into multi-threaded systems.

Because tetconic, climatic, lithologic, or any combincation of these forcings can influence the stability of bedrock meandering rivers,

this study focuses on the role of lithology in maintaining single-thread channel stability.

To explore threshold behavior, I utilize a 1-D bedrock incision model adapted from Howard and Knutson (1984) by Profs. Sarah Schanz and Briany Yanites.

Supported in full by an NSF-funded research grant awarded to Prof. Sarah Schanz, this project was carried out from junior summer (2022) to senior spring (2023) at Colorado College.

Introduction

The role of lithology in active bedrock meandering rivers can be partitioned into three primary mechanisms:

Figure 1. Slaking bedrock of the Roslyn Formation in central Washington State, USA. Image provided by Prof. Sarah Schanz.

- Rock strength and erosion resistance: Stronger and more deeply exhumed lithologies exhibit greater erosion resistance and maintain stable channel forms more readily than younger, softer rocks (Bursztyn et al., 2015).

- Channel width control: An inverse relationship exists between rock strength and channel width, with stronger substrate strength typically associated with narrower channel widths (Allen et al., 2013).

- Weathering processes: Differential weathering processes such as slaking and freeze-thaw cycles create asymmetry between sub-aerial and submerged bedrock erodibility, promoting channel widening (Montgomery, 2004).

Methods

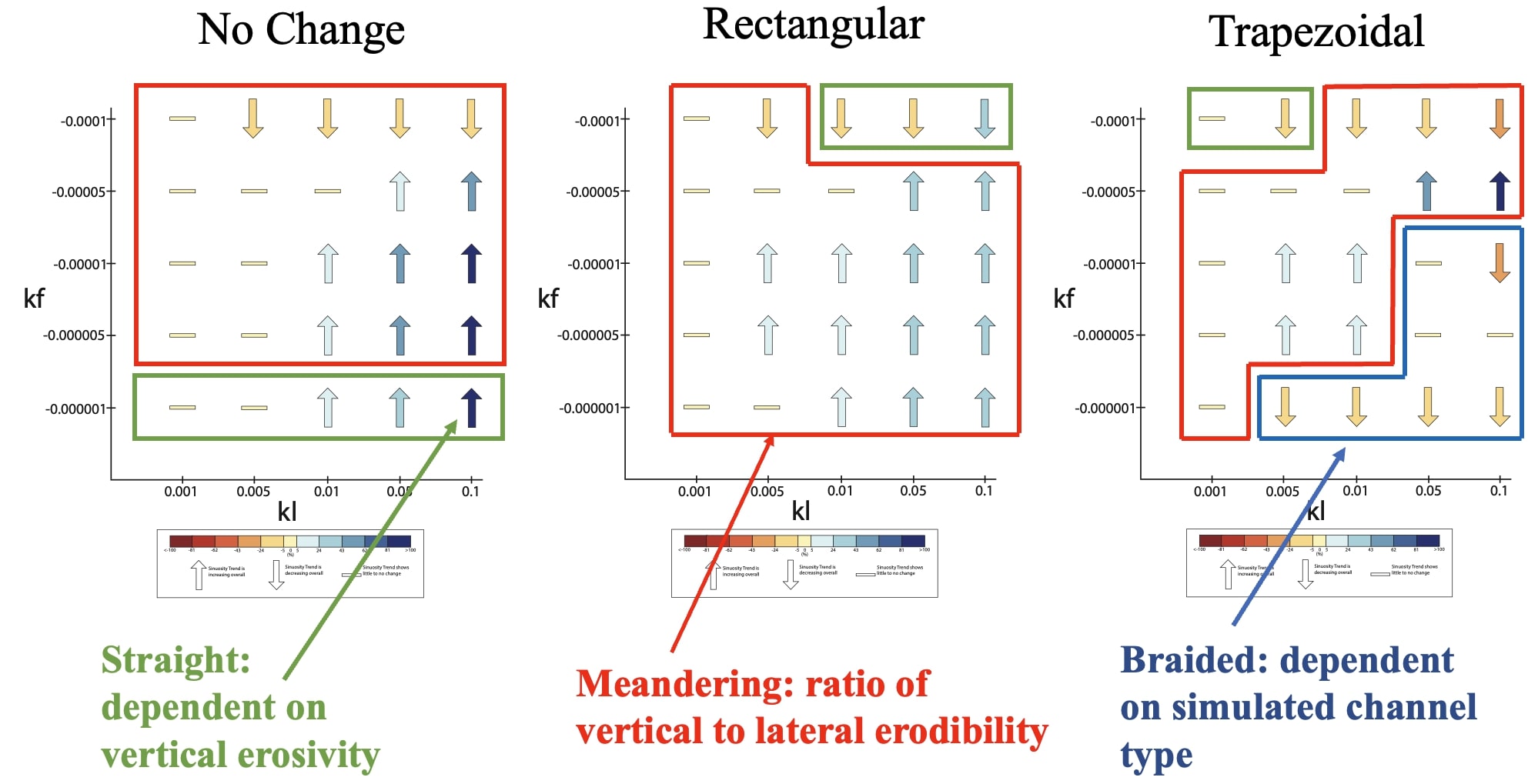

To understand how anisotropic bedrock strength influences river behavior, two key erosional processes that determine channel evolution are quantitatively examined. Lateral erodibility (kl) controls how readily the river can widen its channel through sidewall erosion, while vertical erodibility (kf) governs the rate of downward incision into the bedrock. These parameters are central to understanding where and how erosion occurs, since anisotropic strength allows rivers to preferentially erode along certain directions.

Because these erodibility constants are not well-constrained through field measurements or laboratory experiments, I tested a range of empirically derived values to explore their effects on channel behavior.

The vertical erodibility values tested were -0.000001, -0.000005, -0.00001, -0.00005, and -0.0001, while lateral erodibility values ranged from 0.001 to 0.1 (specifically: 0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1).

Besides, previous models have largely assumed static channel width channel geometry (Leopold & Wolman, 1957), as they are computationally efficient and simple to implment. A key innovation of this model allows the channel width to change with lateral migration and/or channel depth to change with vertical incision. Three distinct channel geometry types are simulated: 1. with constant width and height (no_change) 2. rectanglular 3. trapezoidal. (Figure. 2)

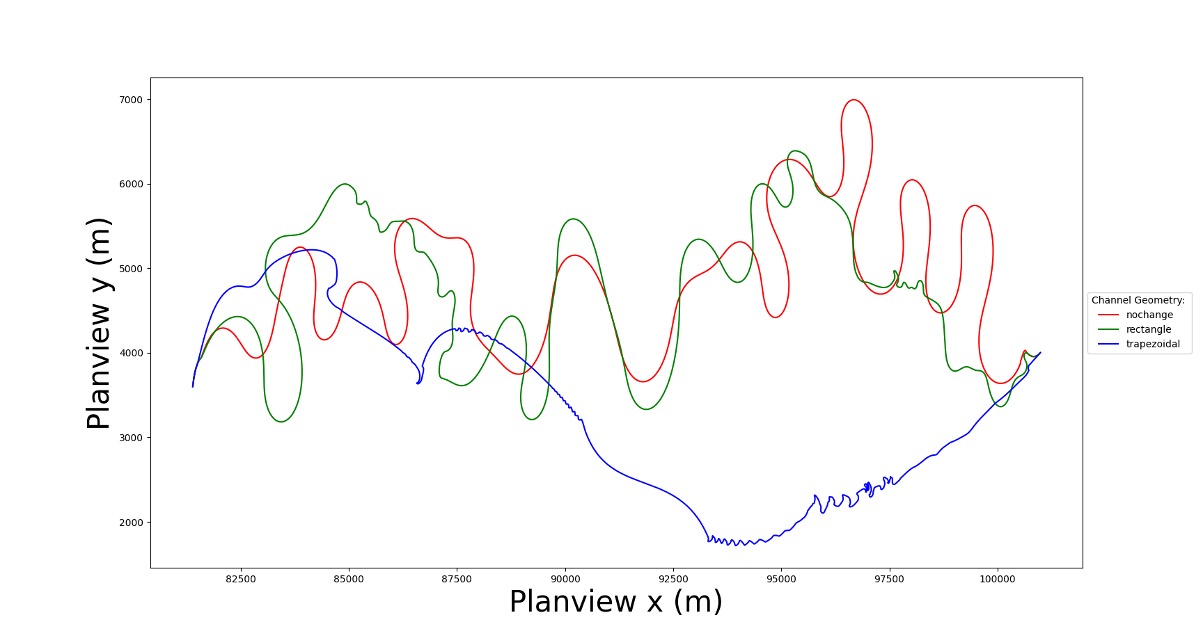

Figure 2. Comparison of planforms at 100 ky for different channel types: no change, rectangular, and trapezoidal. kl, kf, and initial slope held constant at 0.05, -0.000001, and 0.0001, respectively. The trapezoidal channel exhibits high-frequency, low-amplitude oscillations , which are indicators of frequent cutoffs.

Lastly, follwoing traditional geomorphological convetions, channels with a sinuosity greater than 1.5 were considered as meandering rivers.

Insights

A single thread meandering bedrock river can evolve into a straight channel, meandering channel, or transit to exhibit braided patterns, depending on the balance between lateral and vertical erosion rate and the geometry of the river channel.

Figure 3. A total of 125 simulations of channels with different lateral erodibility, vertical erodiblity, and channel geometry, all starting from a sinuosity value of 1.42, were run for 100,000 yrs. The arrows in the figure indicate whether the sinuosity of a partiuclar channel decreases or increases after 100,000 yrs.

References

- Allen, G. H., Barnes, J. B., Pavelsky, T. M., & Kirby, E. (2013). Lithologic and tectonic controls on bedrock channel form at the northwest Himalayan front: BEDROCK CHANNEL FORM, MOHAND, INDIA. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, v. 118(3), p. 1806–1825. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrf.20113.

- Bursztyn, L., Pederson, J. L., Tressler, C., Mackley, R. D., & Mitchell, K. J. (2015). Rock strength along a fluvial transect of the Colorado Plateau: Quantifying a fundamental control on geomorphology. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 429, 90-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.07.042.

- Howard, A. D., & Knutson, T. R. (1984). Sufficient conditions for river meandering: A simulation approach. Water Resources Research, v. 20(11), p. 1659–1667.https://doi.org/10.1029/WR020i011p01659.

- Leopold, L. B., & Wolman, M. G. (1957). River channel patterns: Braided, meandering, and straight (Professional Paper 282-B). U.S. Geological Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/pp282B.

- Montgomery, D. R. (2004). Observations on the role of lithology in strath terrace formation and bedrock channel width. American Journal of Science, v. 304(5), p.454–476. https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.304.5.454.

Research Output